Horse Teeth and Floating: How to Care for Equine Teeth and Estimate Age by Dental Clues

- Horse Education Online

- Jul 23, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Aug 20, 2025

A horse’s mouth is more than a place to park a bit—it is a finely tuned machine that grinds forage into fuel. Healthy horse teeth allow for efficient chewing, which boosts digestion, maintains weight, and ultimately supports athletic performance and longevity. When enamel points develop or teeth wear unevenly, that machine starts to misfire: feed is wasted, gut health suffers, and subtle discomfort can snowball into training and behavior problems.

In this guide you will learn:

Floating fundamentals—what “floating” really means, why it prevents painful edges, and how often each age group needs the procedure

Age-by-teeth techniques—simple visual cues (like Galvayne’s groove and dental stars) that help you estimate a horse’s age with surprising accuracy

Practical tips for scheduling exams, spotting red flags early, and choosing a qualified professional

As we discuss how chewing quality affects nutrient uptake, check out The Basics of Equine Nutrition to see how proper chewing translates to better nutrient absorption.

Anatomy of the Equine Mouth

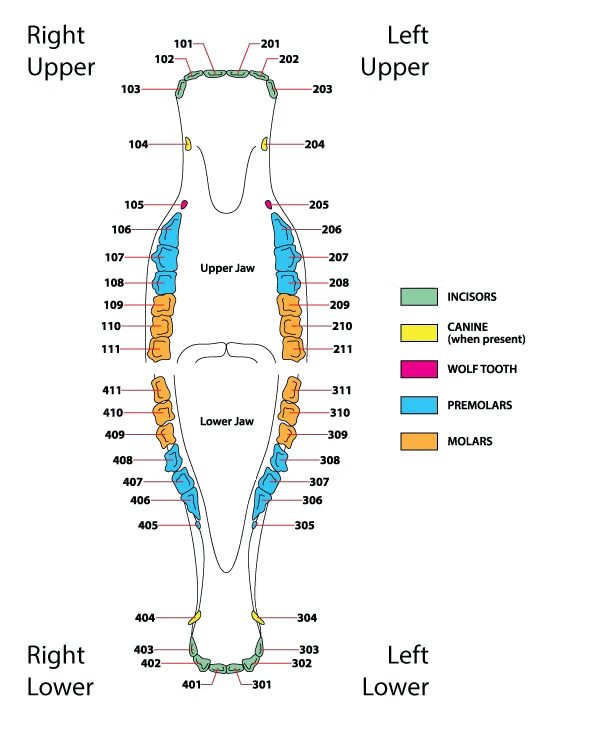

An adult horse carries 36 to 44 teeth—more than most people guess. Those extra grinders and cutters evolved for one job: shredding abrasive forage for up to 16 hours a day. Below is a quick-reference table that shows where each tooth sits, how many erupt, and when they break through the gumline.

Tooth type | Usual count* | Primary job | Deciduous eruption | Permanent eruption |

Incisors | 12 (6 upper / 6 lower) | Snip and pick grass | Birth – 8 mo | 2.5 – 4.5 yr |

Canines | 0–4 (mostly in males) | Weapon & bit stabilizer | None | 4–6 yr |

Wolf teeth | 0–4 (often removed) | Vestigial—can interfere with bit | 5–7 mo | — |

Premolars | 12 | First grinding stage | Birth – 2 mo | 2–4 yr |

Molars | 12 | Final grinding stage | — | 1 – 4 yr |

*Exact totals vary by sex and wolf-tooth presence.

Meet the Players

Incisors sit front-and-center. Their flat tables shear forage before it is passed back to cheek teeth.

Canines appear in roughly 20 percent of mares but in nearly every gelding or stallion—handy to know if you are estimating age by teeth shape.

Wolf teeth are tiny premolars in front of the first cheek tooth; trainers often request extraction because they can bump the bit.

Premolars and molars (the “cheek teeth”) form two long dental arcades that slide past each other like millstones, pulverizing roughage into digestible particles.

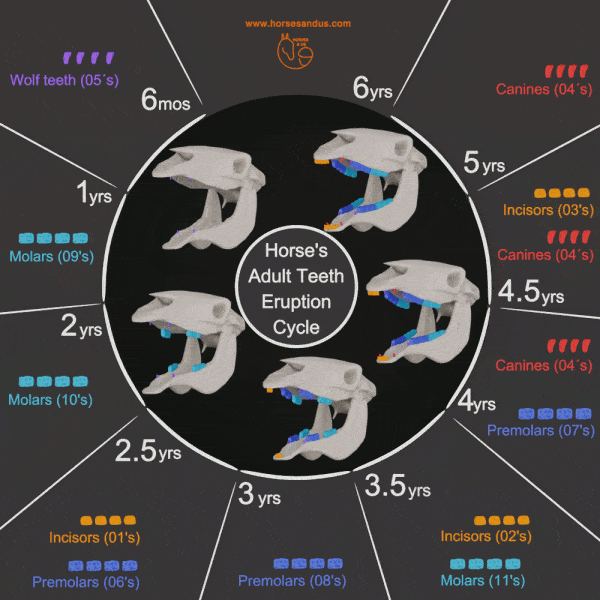

Tooth Eruption Timeline

A foal is born with—or will erupt within days—eight incisors and three premolars in each jaw. By five years of age the last molars have erupted, the canines have finished in males, and the mouth is considered “in full wear.” A handy visual eruption wheel is shown above—save it to your phone for quick reference at the barn.

Example: A two-year-old filly that suddenly drops grain may still be shedding her last deciduous premolars (“caps”). Those loose caps can create sharp edges that cut the cheek—a problem easily caught during a dental exam.

Why Anatomy Matters for Performance

Each millimeter of enamel lost from excessive points can reduce chew time, leading to larger feed particles in the gut and greater colic risk.

Overgrowth on the upper 109 and 209 teeth (“hooks”) can restrict jaw swing, causing poll stiffness that riders often mistake for bit resistance.

Poor lateral excursion from wave mouth reduces saliva production, which in turn slows hay fermentation in the hindgut.

If you notice weight loss despite ample feed, review our nutrition basics and schedule a dental check at the same time—chewing efficiency and nutrient uptake are inseparable.

Quick Self-Check

Run your fingers along the outside of the cheek while your horse is relaxed:

Feel for sharp ridges that press the cheek against molar edges.

Lift the lip and confirm incisors meet evenly; an overjet (“parrot mouth”) needs early veterinary guidance.

Pain-related head-tossing or quidding can mimic systemic illness, so compare with vital-sign norms here: The Horses' vital signs

Pro tip: Keep a simple eruption chart in your tack room. It turns casual barn chatter (“How old is he again?”) into informed management decisions—especially useful when buying or selling horses.

Why Horses Need Their Teeth Floated

Regular floating—smoothing sharp enamel points and correcting uneven wear—keeps a horse’s jaw gliding freely and protects delicate cheek tissue. Left unchecked, small points can grow into saw-like edges that make every mouthful a chore.

What Goes Wrong Inside the Mouth

Problem | Where it forms | Consequence |

Enamel points | Outside edges of upper cheek teeth, inside edges of lower | Cheek or tongue ulcers, shortened chew time |

Hooks | Front of upper 106/206, back of lower 311/411 | Restricted jaw extension, poll stiffness |

Wave mouth | Entire arcade when teeth wear at different rates | Poor lateral excursion, reduced saliva production |

Studies show that horses with severe hooks can lose up to 50 % of normal lateral jaw motion, increasing feed particle size and colic risk.

Signs Your Horse May Need Floating

Dropping grain or rolling hay balls (quidding)

Bit avoidance, rooting, or grabbing the reins

Head-tossing, especially when asked to flex at the poll

Weight‐loss despite adequate forage and The Basics of Equine Nutrition recommendations

Unexplained facial swelling or foul breath

Behavioral changes tied to pain—such as sudden head-tilt while chewing—warrant a quick review of How to Tell if Your Horse Is Sick: Early Signs Every Owner Should Know. Dental discomfort often masquerades as general malaise.

How Often Should You Schedule Floating?

Age / Workload | Exam & float guideline | Rationale |

6 mo – 5 yr | Every 6 months | Deciduous caps shed; rapid tooth eruption |

6 – 15 yr (light work) | Yearly | Mouth is in full wear but points still develop |

6 – 15 yr (performance) | Every 6 – 8 months | Increased bit contact and lateral flexion demands |

16 + yr | Every 6 months | Slower eruption, but tooth roots shorten and fracture risk rises |

These intervals mirror the core recommendations from AAEP Equine Dentistry Guidelines.

Safe Sedation and Equipment Choices

Most horses float best under light standing sedation—commonly xylazine 0.5 mg/kg or detomidine 0.01 mg/kg IV, often paired with butorphanol for additional analgesia. A padded dental stand keeps the head level, and modern power floats finish the job in 10–15 minutes with minimal heat build-up. Manual rasps still have a place for small touch-ups or thin enamel shells near the infundibulum.

Example:

A 1,000 lb Quarter Horse receives 0.25 ml of detomidine (10 mg/ml) for a 10-minute float. Heart rate drops from 40 bpm to a steady 32 bpm, allowing safe cheek inspection without twitching.

Floating Myths vs Facts

Myth | Reality |

“Young horses never need floating.” | Caps and fast-erupting teeth create razor-sharp points by age two—early checks prevent lifelong imbalance. |

“Floating hurts.” | Under light sedation and with water cooling, most horses show lower cortisol after the procedure than before. |

“Hand tools are safer than power tools.” | Torque-limited power floats remove enamel precisely and quickly, reducing mouth fatigue; success depends on the operator, not the tool. |

When dental pain mimics back soreness or inconsistent lead changes, review our Comprehensive Guide to Equine Lameness for a holistic work-up. Proper dentistry often resolves “mystery” training issues faster than saddle adjustments alone.

Aging a Horse by Its Teeth

Learning to “read” teeth lets you verify purchase papers, manage nutrition for seniors, and keep accurate medical records. While no field method is perfect, the guidelines below will bring you within a year or two of a horse’s true age until roughly its mid-teens.

Estimated age | Key incisor features | Cup / dental-star status | Galvayne’s groove* | Incisor angle |

2½ – 3 yr | Permanent central incisors just erupted; still short | Deep cups present | Absent | Nearly vertical |

5 yr | All six permanent incisors in full wear, oval tables | Cups shallow on centrals | Absent | Slight slope |

7 – 10 yr | Centrals round; intermediates oval | Dental star appears on centrals at ~8 yr | Groove begins at gum line (often 10 yr) | Noticeable slope |

15 yr | Centrals triangular; cups gone from all | Stars centered on tables | Groove halfway down tooth | 15–20° |

20 yr | Tables nearly triangular; teeth shorter | Stars enlarged, dark | Groove extends full length | 25–30° |

*Galvayne’s groove forms on the upper corner incisor: visible at the gum line around ten, halfway down at fifteen, and the full length by twenty.

Need a deeper dive into the structure and function of the equine skull? Our Equine Anatomy Certification includes detailed diagrams and instructor-guided lessons covering incisors, premolars, and age-related changes. Perfect for owners, students, or anyone prepping for vet tech exams.

Step-by-Step Field Check

Flip the lip and confirm all six permanent incisors are present (by five years).

Look for cups—dark, hollow centers that disappear from the centrals first.

Find the dental-star, a yellow-brown line that replaces each cup as wear continues.

Slide a fingertip along the outside of the upper corner incisor; feel or see Galvayne’s groove.

Gauge the angle where upper and lower incisors meet. More slope = more years.

Example:

A gelding shows no cups on any incisors, a dental-star midway across each table, and Galvayne’s groove halfway down. Incisor angle sits at roughly 20 degrees. Those clues point to about fifteen years old—close enough for health-care planning and sales disclosures.

Accuracy tip: After twelve years, wear patterns diverge with diet, sand content, and pasture type. Use age estimates for management decisions, not competition eligibility.

Keep an Eye on the Cheek Teeth Too

Premolars and molars shorten over time; seniors can lose grinding surface and drop weight even with perfect incisors. In those cases, adjust ration form as outlined in The Basics of Equine Nutrition and schedule more frequent floats.

Downloadable Aging Chart

Need a barn-aisle reference? Grab this Horse Teeth Aging Chart PDF—printable at letter size, cell-phone friendly.

Common Dental Problems and Their Consequences

Even a tiny ridge of enamel can snowball into systemic problems if it hurts every time your horse chews or accepts the bit. Below is a quick-scan table of the issues practitioners see most often, why they form, and what happens if you ignore them.

Problem | Age group most at risk | How it develops | Real-world consequence |

Sharp points on cheek teeth | All ages, especially hay-fed stabled horses | Natural lateral jaw motion pushes enamel beyond the softer dentin, creating razor-edges on the outer uppers and inner lowers | Cheek ulcers, quidding, head-tilt while eating; performance horses may suddenly toss the head or resist lateral flexion |

Retained deciduous caps (baby-tooth shells) | 2 – 5 yr | Permanent premolars erupt but fail to shed the milk-tooth layer | Pain when biting, uneven wear that starts a lifelong wave mouth unless removed |

Hooks and ramps | Horses with parrot mouth; any horse on long-stem hay with little grazing | Overlong tooth meets no opposing wear partner | Limited forward jaw slide; poll tension mistaken for back soreness—see Comprehensive Guide to Equine Lameness for crossover evaluation |

Wave mouth | Mid-teens horses or those whose caps weren’t removed | Cascade of high-low grinding surfaces | Shortened chew time, large feed particles in manure, weight loss despite high-calorie rations |

Lost or fractured cheek tooth | Seniors (20 + yr) or horses that crib | Infundibular caries, root decay, or torsional stress | Food pocketing in the socket → sinus infection; dramatic drop in body-condition score (review Equine Metabolic Syndrome sidebar if weight rebounds unevenly) |

Case example:

A 17-year-old gelding dropped from body-condition score 5 to 4 in six weeks. Manure showed long hay fibers 1 – 2 cm in length (ideal is < 0.5 cm). Dental exam revealed a missing 209 molar that created a wave. After extraction site care and a pelleted senior ration, weight stabilized within 30 days.

How Dental Pain Mimics Other Problems

Colic risk increases: feed size > 2 mm doubles large-colon transit time.

Behavioral “naughtiness”: head-shaking, rooting, or refusing the bit often vanishes 48 hours after a float.

Misdiagnosed lameness: uneven rein contact can make a horse appear one-sided behind; always rule out mouth pain before changing shoeing angles.

For a refresher on spotting subtle health shifts—such as dull coat, decreased appetite, or elevated digital pulse—scan The Horse’s Vital Signs article. If dehydration complicates post-procedure recovery, review How to Tell If a Horse Is Dehydrated for quick skin-turgor checks and electrolyte tips.

Numbers That Matter

1–3 mm: average height of enamel points removed during routine float

8–12 weeks: time it takes for sharp ridges to re-form in young horses with rapid eruption if no float is scheduled

15 %: reduction in dry-matter intake documented when painful hooks limit lateral jaw excursion

Keeping the mouth comfortable is cheaper than treating the ulcers, choke episodes, or impaction colics that follow neglected dentistry. In the next section we’ll put theory into practice by building a Dental-Care Schedule that matches your horse’s age, workload, and living situation.

Creating a Dental-Care Schedule

Establishing a written dental plan keeps small issues from turning into costly emergencies. Use the guide below to tailor exam frequency to each horse’s age, workload, and living conditions.

Category | Recommended interval | Why it matters | Notes |

Foals 6 mo – 2 yr | Visual mouth check every 6 mo | Shed caps correctly, catch congenital bite issues early | Float only if sharp points ulcerate the cheek |

Young horses 2 – 5 yr (under saddle) | Full dental exam and float every 6 mo | Rapid eruption + bit training combine to form points quickly | Sedation doses are small; budget ≈ $120 – $180 per visit (Ontario 2024 rates) |

Mature leisure horses 6 – 15 yr | Annual exam and routine float | Mouth is in full wear but enamel still outgrows dentin | Mark the date in your health-record app alongside vaccinations and “The Horse’s Vital Signs” log |

High-performance horses (dressage, barrels, race) | Exam every 6 – 8 mo | Collection and flexion amplify discomfort from tiny hooks | Ask the vet to record incisor angles for future age tracking |

Seniors 16 + yr | Exam every 6 mo, sometimes 4 mo for missing teeth | Roots shorten; waves and loose molars appear | Switch to soaked cubes once grinding surface drops below 70 % (per AAEP senior-care sheet) |

Annual Dental-Exam Checklist

Visual inspection of incisors, canines, and cheek teeth with bright head-lamp

Palpation for loose caps or fractured enamel

Mirror (or oral endoscope) run along palatal surface to spot infundibular caries

Lateral jaw excursion measured in millimetres before and after float

Weight, body-condition score, and manure particle size recorded (compare with “How to Tell If Your Horse Is Dehydrated” if manure looks dry)

Photo of upper corner incisor saved to the cloud folder for age-tracking reference

Example:

After one year on an eight-month float cycle, a show jumper’s lateral excursion improved from 9 mm to 13 mm, bit acceptance scores rose 20 % in rider logs, and the horse gained 35 lb of topline without increasing grain (see “The Basics of Equine Nutrition” for why improved chewing boosts calorie extraction).

Red-Flag Monitoring Between Visits

Sudden change in hay preference or longer eating times

Small cigar-shaped wads of partially chewed hay on stall floor (quidding)

Unexplained weight loss despite caloric increase—rule out dental pain before testing for Equine Metabolic Syndrome.

Head-tilt while grinding or holding the jaw to one side

Subtle attitude shifts such as reluctance to flex at the poll or shortened stride on one lead.

Document these signs in the barn’s health journal; trends matter more than single observations.

Scheduling Pro Tips

Pair the spring float with Coggins testing and vaccinations to minimize haul-in trips.

Use a shared Google Calendar for reminders—invite your vet and barn manager so sedative withdrawal times are clear before competitions.

After floating, offer soaked beet pulp and monitor water intake (review “How to Tell If a Horse Is Dehydrated” for quick checks).

A proactive schedule costs less than one impaction colic, and horses that chew comfortably maintain weight, shine, and train happily year-round.

Want ongoing support and access to our full learning library? Our membership plans unlock everything—from anatomy breakdowns to nutrition blueprints. Explore Horse Education Online Memberships to level up your equine care knowledge at your own pace.

Cost and Professional Options

Floating fees can vary widely, but a little budgeting clarity helps you plan dental care instead of postponing it.

Service | Typical cost (USD) | What’s included | Notes |

Basic hand-float (barn call) | $100 – $150 | Oral exam, manual rasping of points | Suitable for leisure horses with minor edges |

Power-float with light sedation | $180 – $250 | Sedative, speculum, motorized grinding, occlusion check | Most common choice for performance horses; in-out time ≈ 20 min |

Advanced corrective float (hooks, waves) | $250 – $400 | Full-mouth balance, incisor alignment, bite-plane adjustment | May require two sessions 3-4 months apart |

Wolf-tooth extraction (each) | $40 – $80 | Local block, extraction, after-care advice | Often done with the first float on young stock |

Dental radiographs (head-side unit) | $75 – $120 | Digital images to assess roots, sinus health | Recommended before pulling a fractured molar |

Vet or Certified Equine Dentist?

Veterinarian:

Can sedate, prescribe antibiotics, and take radiographs on the spot.

Ideal for complex extractions, geriatric mouths, or horses with systemic issues like Equine Metabolic Syndrome that may need pain-management adjustments.

Certified Equine Dentist (non-vet):

Often travels with portable power-float gear and a padded headstand, keeping barn call costs down for routine work.

Must legally partner with a vet for sedation in many states and provinces—confirm the protocol before booking.

Field example:

A four-horse barn in Ontario scheduled annual floats with a dental technician. The attending vet provided xylazine and butorphanol sedation (≈ $25 per horse). Total invoice: $780, or $195 per horse, including a quick wolf-tooth pull on the youngest gelding.

Portable Power-Float Advantages

Battery packs run 4–6 floats on one charge—no search for outlets in remote sheds.

Torque-limiter prevents over-grinding; most units stop at 6 N·cm, removing only enamel, not dentin.

Water-cooling spray keeps tooth surface < 40 °C, protecting pulp tissue.

If your horse lives out 24/7, ask whether the practitioner carries a lightweight dental stand that folds into the truck bed; it reduces neck fatigue during the procedure and keeps the speculum level for better visibility.

Further Reading: Classic Insights on Horse Care

Looking to go beyond floating and into the roots of equine care? These timeless reads offer practical knowledge and context for anyone serious about horse health and anatomy.

Covers jaw mechanics and tooth alignment from a farrier’s view—useful for understanding how floating fits into total body balance.

Includes practical feeding and dental-care strategies from the pre-modern era—pairs well with our Equine Anatomy Certification.

🐴 Browse more historic and technical titles in our full Book Collection.

Conclusion

A smooth, balanced mouth lets the jaw glide, the gut work efficiently, and the reins stay light. By pairing a written dental-care schedule with informed professional help—whether a veterinarian or certified equine dentist—you’ll prevent small enamel points from turning into weight-loss, colic, or frustrating training plateaus. Take a minute this week to estimate each horse’s age by its teeth, note that number in your health log, and book the next float before sharpening edges steal performance.

FAQ: Horse Teeth, Floating, and Aging

Can miniature horses follow the same dental schedule as full-size breeds?

Yes, though their mouths are smaller, minis have the same tooth types and can develop sharp points, hooks, and wave mouth. Floating frequency is based on eruption rates and wear—not size. Minis often benefit from biannual checks due to crowding.

Do donkeys and mules require different floating techniques?

Slightly. Their tooth anatomy is similar but often denser and shaped differently, especially in mules. Always work with a provider experienced in longears, and monitor for signs like quidding or jaw resistance.

How long does a floating session usually take?

A routine power float takes 15–30 minutes, including sedation and prep. More complex cases (e.g., wave correction or extractions) may take longer. Light sedation allows for safer and more thorough work.

Can improper chewing affect nutritional absorption?

Absolutely. Poor mastication leads to larger feed particles and inefficient digestion. This can mimic malnutrition or Equine Metabolic Syndrome symptoms. Learn more in The Basics of Equine Nutrition.

Is power floating better than hand floating?

Not always—it depends on the practitioner’s skill. Power tools allow faster, more even corrections and are ideal for wave mouth or tight cheek space. Hand floats are still useful for quick touch-ups or horses with very thin enamel.

How soon after floating can I ride my horse?

Most horses can return to light work the next day if no extractions or advanced corrections were performed. Watch for any jaw soreness or bit sensitivity. Always check hydration—see How to Tell If a Horse Is Dehydrated.

What sedatives are commonly used and are they safe?

Xylazine, detomidine, and butorphanol are commonly used, offering short, reversible sedation for standing floats. When administered correctly by a vet, they are safe and well-tolerated. Monitor recovery closely, especially in older or metabolically challenged horses.

Comments