The Equine Nervous System

- Horse Education Online

- Mar 3, 2025

- 17 min read

Updated: Sep 29, 2025

The nervous system is one of the most complex and essential systems in the horse’s body, controlling everything from movement and reflexes to perception and behavior. It serves as the communication network, transmitting signals between the brain, spinal cord, and the rest of the body. Without it, a horse could not respond to its environment, coordinate its gaits, or even maintain basic bodily functions.

Understanding the equine nervous system is crucial for horse owners, trainers, and veterinarians, as it helps in diagnosing neurological disorders, improving training methods, and ensuring the overall well-being of the horse.

Once you have finished reading this article, take the self-assessment quiz, then move on to "The Equine Nervous System: Part 2 - Diving Deeper" to continue learning.

TL;DR — Common Equine Neurological Disorders

Red flags: inconsistent ataxia (worse on small circles/backing), toe drag, head tilt/uneven blink, trouble swallowing, weak tail/urine dribble, sudden behavior change. Stop riding, video, check vitals, call your vet.

Likely culprits (field patterns):

Wobbler (CVM): young/tall or arthritic neck → fore/hind ataxia, toe drag, worse on tight turns.

EPM: asymmetric weakness/muscle loss; “odd” one-sided gaits.

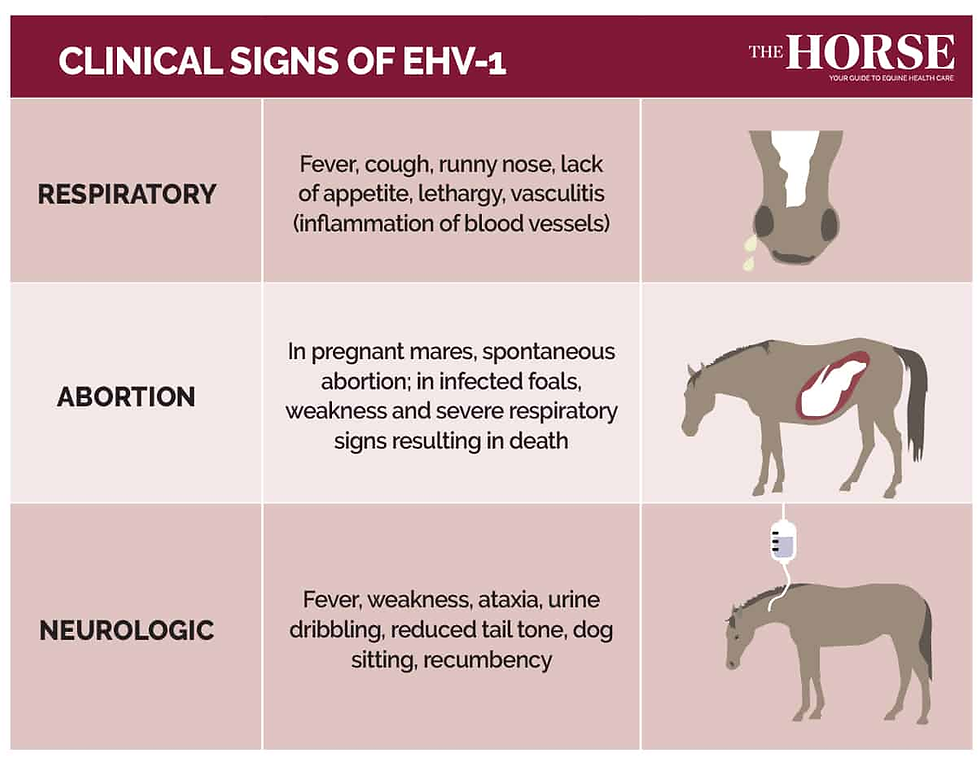

EHV-1 neuro: recent fever/outbreak → sudden hind ataxia + urine issues; isolate.

Stringhalt: jerky high hind step, esp. when backing/turning.

Shivers: tremor + hyperflexion of a hind when backing or lifting the foot.

Others to know: EDM/EDX (low Vit E; symmetric ataxia), Polyneuritis equi (flaccid tail/anal tone), THO (facial paralysis, head tilt, eye risk).

Want a quick check? Try our Neuro Screen & Localization Assistant to log signs and print a vet-ready summary.

Do now:

No riding. 2) Record straight line, both circles, backing, small hill if safe.

Vitals: temp/HR/RR, mucous membranes → compare to your normal (see The Horse’s Vital Signs, Average Heart Rate).

Call your vet; EHV-1 signs → isolate immediately.

Keep learning: Part 2 (reflex grading & assessment flow) → Equine Nervous System: Part 2 — Diving Deeper.

Overview of the Equine Nervous System

The horse’s nervous system is the body’s command-and-communication network. It senses what’s happening (inside and out), decides what matters, and coordinates every movement—from blink and swallow to canter lead and trailer loading. For practical purposes, think in three layers that work together every second:

1) Central Nervous System (CNS): brain + spinal cord

Brain (cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem) processes information, learns patterns, times and smooths movement, and runs life-support reflexes (breathing, swallowing, heart-rate control).

Spinal cord is the main highway, carrying signals to and from specific body regions (neck/forelimbs → cervical; trunk/hindlimbs → thoracic/lumbar; tail/pelvis → sacral). Local cord problems cause local signs (e.g., forelimb toe-drag with cervical issues).

2) Peripheral Nervous System (PNS): all the “wires” out to the body

Sensory (afferent) nerves bring information in—touch, pain, temperature, body position.

Motor (efferent) nerves send commands out to muscles for posture and movement.

Cranial nerves (12 pairs) handle special senses and head/neck functions (vision, balance, facial movement, swallowing). Simple barn checks (menace, palpebral blink, tongue tone) can hint where trouble is—document and call your vet.

3) Autonomic vs Somatic: automatic control vs voluntary action

Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) has two branches in constant balance:

Sympathetic = “fight-or-flight” (alert, higher heart rate, blood to muscles).

Parasympathetic = “rest-and-digest” (recovery, gut motility, normal heart rate).

Somatic system manages voluntary skeletal muscle—everything from halting square to lateral work.

Owner takeaway: When you notice coordination changes, odd behavior, or cranial-nerve clues (head tilt, uneven blink, difficulty swallowing), pair those observations with baseline vital signs and average heart rate to judge urgency—then involve your veterinarian early.

The Central Nervous System (CNS)

The Brain

The horse’s brain is relatively small compared to its body size, weighing about 1.5 pounds (650-700 grams). However, it is highly developed in areas responsible for movement, coordination, and survival instincts.

The brain is divided into several key regions:

Cerebrum – The largest part, responsible for thought, decision-making, memory, and sensory processing.

Cerebellum – Controls balance, coordination, and fine motor skills, ensuring smooth and precise movements.

Brainstem – Connects the brain to the spinal cord and regulates automatic functions such as heartbeat, breathing, and digestion.

While horses are highly intelligent and capable of learning, their brains are wired primarily for reactive behavior rather than deep reasoning, making them reliant on instincts and conditioned responses.

The Spinal Cord

The spinal cord extends from the brainstem down the length of the spine, acting as a major highway for nerve signals. It transmits information between the brain and the rest of the body, coordinating reflexes and movement.

Cervical region – Controls the neck and forelimbs.

Thoracic and lumbar regions – Responsible for trunk and hindlimb movement.

Sacral region – Governs tail and pelvic functions.

If the spinal cord is damaged, it can result in partial or complete paralysis, depending on the severity of the injury.

The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

The PNS consists of cranial and spinal nerves that branch out from the CNS, carrying signals to and from different parts of the body.

Sensory and Motor Nerves

The PNS is divided into two functional components:

Sensory (Afferent) Nerves – Transmit signals from the body to the brain, allowing the horse to detect pain, pressure, heat, and movement.

Motor (Efferent) Nerves – Carry signals from the brain to the muscles, enabling movement and coordination.

A horse’s acute sensory perception allows it to respond quickly to stimuli, a survival trait developed over millions of years.

Cranial Nerves

Horses have 12 pairs of cranial nerves that emerge from the brain and control functions such as:

Sight (Optic nerve)

Hearing and balance (Vestibulocochlear nerve)

Facial movement and expression (Facial nerve)

Swallowing and digestion (Vagus nerve)

Damage to cranial nerves can result in head tilt, difficulty swallowing, or loss of coordination.

Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

The ANS is responsible for regulating involuntary functions such as heart rate, digestion, and sweating. It is divided into:

Sympathetic Nervous System – Controls the fight-or-flight response, increasing heart rate and alertness.

Parasympathetic Nervous System – Governs the rest-and-digest state, promoting relaxation and energy conservation.

This balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity is critical for maintaining a horse’s overall health and ability to respond appropriately to stressors.

Neurological Reflexes and Responses in Horses

Reflexes are fast, built-in responses that help you localize a problem (brain, cranial nerves, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves). They’re screening tools—not diagnoses—but when you record them well, your vet can triage faster.

Safety & setup (60-second prep)

No riding, halter + lead, level footing, calm handler, a quiet helper if available.

Stand near a wall or fence for backing/circling tests (reduces drift).

If the horse resists, shows pain or distress, or you feel unsafe—stop.

Quick cranial-nerve panel

Reflex / Check | How to do it (gently) | Normal | Abnormal flags (call your vet) | Likely area |

Menace response (CN II → VII) | Hand “swipe” toward one eye (don’t touch lashes; don’t create wind) | Blink and slight head withdraw | No blink on one side; inconsistent between sides | Vision pathway/forebrain or facial motor |

Palpebral blink (CN V ↔ VII) | Light tap at inner/outer eyelid corner | Prompt blink | Weak/absent blink; side difference | Trigeminal/facial nerve |

Pupil light reflex (CN II ↔ III) | Shade one eye, then add light and observe pupil | Constriction to light | Sluggish/uneven pupils, anisocoria | Optic/oculomotor pathway (autonomic) |

Facial symmetry (CN VII) | Look at ears, nostrils, lips at rest | Even tone and movement | Ear/lip droop, nostril collapse | Facial nerve deficit |

Tongue tone (CN XII) | Gently grasp tongue; assess resistance | Firm tone, retracts readily | Floppy or asymmetric | Hypoglossal nerve/motor |

Gag/swallow (CN IX, X) | Offer small sip of water/paste under vet guidance | Swallow cleanly | Coughing, nasal reflux, dysphagia | Brainstem/cranial nerves |

Head tilt / nystagmus (CN VIII) | Observe at rest and while moving slowly | Head level, eyes steady | Tilt, flicking eyes, balance loss | Vestibular system |

Eye protection matters: if blink is weak, protect the cornea (shade, vet-approved lubrication) and seek care promptly.

Spinal & segmental reflexes

Reflex | How to do it | Normal | Abnormal flags | What it hints |

Cutaneous trunci (panniculus) | Lightly pinch skin over mid-ribcage and along trunk | Skin twitch under your pinch | Patchy/no twitch behind a level | Possible lesion at/above the “no-twitch” level |

Perineal (anal) reflex & tail tone | Visual check of anal “wink”; gentle tail lift | Crisp wink, firm tail | Flaccid tail, poor tone, soiling | Sacral nerve roots/cauda equina |

Cervical pain screen | Slow, small neck flexions L/R/down | Moves freely | Pain/guarding, resentment | Cervical OA/stenosis (wobbler mimic) |

If pain is evident, don’t force range—note it and stop.

Proprioceptive (postural) reactions

These reveal ataxia (incoordination) that often worsens on tight circles, backing, slopes, or with eyes partially occluded (do not blindfold).

Test | How to do it | Normal | Abnormal (red flags) | Localization clues |

Tight circles | Walk small circles both ways | Even steps, tracks under | Wide swing of hind, crossing errors, stumbling | Cervical/long-tract pathways, cerebellar |

Backing | 4–6 slow steps straight back | Diagonal rhythm, steady | “Dog-sitting,” knuckling, delayed placing | Cervical cord, cerebellar |

Tail pull while walking | Gentle lateral pull on tail mid-walk | Resists, returns straight | Drifts without correcting | Hind motor pathways/spinal cord |

Placing / toe drag | Watch toes on straight/turns | Clear flight arc | Toe scuffing/drag, worn toes | Segmental myelopathy, EPM, cervical |

Slope test (if safe) | Walk short gentle incline/decline | Maintains posture | Worsening sway/stumble downhill | Long-tract deficits |

Interpreting patterns

Asymmetry (one side clearly worse) → think EPM, THO (if facial/ear signs), focal lesions.

Symmetric ataxia in a young horse with normal muscle bulk → consider EDM/EDX (vitamin E–linked).

Sudden hind ataxia + urine dribble + weak tail tone, often after fever/new arrivals → EHV-1 neurologic (isolate).

Forelimb toe drag + neck pain → consider cervical compression/arthritis (wobbler spectrum).

Jerky, high hind step when moving off/backing → stringhalt; tremor + hyperflexion when backing or picking up foot → shivers.

Simple 0–3 field severity note (for your video captions)

0 = normal; 1 = subtle (seen on small circle/backing); 2 = obvious at walk; 3 = unsafe/near-fall.Use the same ground, same handler, left + right, straight + circle + backing, and say the date/time on camera.

When to stop and call the vet now

New trouble swallowing, head tilt, uneven pupils/blink, urine dribbling, recumbency, or rapidly worsening ataxia.

Any neuro signs after a fever or in barns with new arrivals (EHV-1 risk) → isolate immediately.

Add objective context with baselines: The Horse’s Vital Signs and Average Heart Rate.

How this ties into training

Clean reflexes and consistent postural reactions predict learnability and balance. If arousal is high, reflexes can look “louder” (sympathetic bias).

If a horse fails basic postural checks, don’t drill the skill—shrink the task, chase relaxation, and seek assessment. See Part 2 for flow and grading: The Equine Nervous System — Part 2: Diving Deeper.

Common Equine Neurological Disorders

Neurologic disease shows up as incoordination, weakness, odd gaits, cranial-nerve changes (blink, swallow, head tilt), behavior shifts, or sudden performance drops. Use the summary table first, then scan the short disorder briefs. When in doubt, stop work, record video, check vital signs and heart rate, and call your vet.

Fast differential table

Condition | What it is (plain English) | Typical signalment / trigger | Hallmark field signs | Simple barn checks (not a diagnosis) | Urgency |

Wobbler syndrome (CVM/CSM) | Neck vertebrae compress the spinal cord | Young, fast-growing, tall TB/WB colts; also older with arthritis | Ataxia front/back, worse on tight circles & backing; toe drag | Tail-pull weakness; sway on incline; uneven placing | Prompt vet; avoid risky riding |

EPM (Sarcocystis neurona, sometimes Neospora hughesi) | Protozoal infection of brain/spinal cord | Any age; pasture/possum exposure (NA) | Asymmetrical weakness, muscle loss, odd gaits | Place feet cross-over while tail-pull—side differences stand out | Prompt vet; earlier tx = better |

EHV-1 neurologic | Herpesvirus inflames spinal cord blood vessels | Often after fever/outbreak; barns with new arrivals | Sudden ataxia, urine dribbling, weak tail tone; often both hinds | Check temp history; tail/anal tone ↓ | Urgent isolation + vet |

Stringhalt | Neuromuscular hyperflexion of hind limb | Any; “Australian” form linked to certain weeds | Jerky high step when moving off/backing; worse when excited | Walk/back slowly—watch one hind snap up | Vet; many improve with time |

Shivers | Progressive movement disorder affecting hindquarters | Drafts, WBs; often tall, young adults | Tremor + hyperflexion of hind when backing or picking up foot; tail raised | Ask to back a few steps—look for tremor/hold | Vet; management over cure |

EDM/EDX (degenerative myeloencephalopathy) | Neurodegeneration linked to low Vit E | Young horses; limited access to green forage | Symmetric ataxia without muscle loss | Neuro signs but good muscle bulk; low Vit E possible | Vet work-up; supplementing may help early |

Polyneuritis equi (cauda equina neuritis) | Immune-mediated nerve root inflammation | Adults; waxing/waning | Tail paralysis, weak anal tone, urine/fecal issues | Tail hangs flaccid; perineal sensation ↓ | Prompt vet |

Temporohyoid osteoarthropathy (THO) | Bony change near ear → nerve deficits | Adults; often ear/upper airway history | Facial paralysis, head tilt, corneal ulcers (can’t blink) | Menace/blink asymmetry; ear pain | Prompt vet; eye protection |

Cervical trauma/arthritis | Injury or OA narrowing the canal | Any; older performance horses | Neck pain + forelimb ataxia/weakness | Pain on neck flexion; resent bit/poll work | Vet imaging needed |

Toxic/metabolic mimics (e.g., hepatic encephalopathy) | Body-wide illness affecting brain | Any; recent feed change, illness | Depression, aimless wandering, odd behavior | Check mucous membranes, temp, HR | Urgent vet; treat cause |

Owner note: “Ataxia” means incoordination—feet land in the wrong place at the wrong time. It usually worsens on tight circles, backing, slopes, or with eyes closed (don’t blindfold—just pick shaded/low-stim settings).

Want a quick check? Try our Neuro Screen & Localization Assistant

Wobbler Syndrome (Cervical Vertebral Malformation / Stenotic Myelopathy)

Neck vertebrae compress the spinal cord, disrupting signal flow. Young, tall, fast-growing horses are classic, but older horses with cervical arthritis can look similar.

What you’ll see: inconsistent, “floaty” hind or fore placement, worse on small circles, backing, or downhill; toe drag; delayed pro-/retro-placing.

What to do now: stop ridden work, record video (straight line, circles, backing), and call your vet.

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): neuro exam + cervical imaging (X-ray/myelogram/CT), diet/growth management, surgery (ventral stabilization) or medical management in select cases.

Prognosis: variable; earlier identification + appropriate management improves safety.

Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis (EPM)

Protozoa (mostly Sarcocystis neurona in North America) inflame the spinal cord/brain. Signs are often asymmetric and can look like training issues early.

What you’ll see: one-sided weakness or muscle loss, stumbling, odd tail carriage, subtle cranial-nerve changes.

What to do now: note onset timeline and stressors; check temperature history; call your vet.Diagnosis & care (vet-led): neuro exam; serum/CSF antibody ratios; approved antiprotozoals; anti-inflammatories; vitamin E support.

Prognosis: good if caught early; residual deficits possible—retraining helps the cerebellum “re-learn” timing.

Equine Herpesvirus-1 (Neurologic Form)

A contagious herpesvirus can cause vasculitis in the spinal cord. Often follows fever, respiratory signs, or new-horse introductions.

What you’ll see: sudden hind-end ataxia, dog-sitting, weak tail/anal tone, urine dribbling.

What to do now: isolate immediately, monitor temp twice daily, and call your vet.

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): PCR on nasal swabs/whole blood; anti-inflammatories, nursing care, bladder support; biosecurity for the barn.

Prognosis: variable; some recover, severe cases risk recumbency.

Stringhalt

Abnormal nerve/muscle control produces exaggerated hind flexion, especially when backing, turning, or excited. Some pasture-associated cases improve after removing the suspected plants; others are idiopathic.

What you’ll see: sudden high “snap” of a hind limb; horse may settle at the trot.

What to do now: reduce triggers, keep footing even, and consult your vet.

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): clinical pattern; rule out pain; management, rehab; surgery (tenectomy) in select cases.

Prognosis: many improve; some persist at low level.

Shivers

A chronic movement disorder affecting hindquarters (sometimes fore). Common in drafts/Warmbloods.

What you’ll see: trembling and hyperflexion of a hind limb when asked to back or when lifting the foot; tail may elevate.

What to do now: avoid forcing the limb up; schedule vet evaluation; trim/shoe with low-stress handling.

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): clinical pattern; management emphasizes calm handling, consistent exercise, footing; investigate concurrent orthopedic issues.

Prognosis: managed, not cured; severity often waxes/wanes.

EDM/EDX (Equine Degenerative Myeloencephalopathy / Neuroaxonal Dystrophy)

Neurodegenerative disease linked to low vitamin E status in young horses; tends to be symmetric (both sides equally).

What you’ll see: mild to moderate ataxia without notable muscle loss; “just not coordinated.”

What to do now: discuss vitamin E testing with your vet; don’t start supplements blindly (form and dose matter).

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): neuro exam; serum α-tocopherol; management with natural-source vitamin E and turnout.

Prognosis: progression varies; earlier nutritional support helps.

Polyneuritis Equi (Cauda Equina Neuritis)

Inflammation of multiple peripheral nerves—particularly those to the tail and perineum.

What you’ll see: flaccid tail, weak anal tone, fecal retention/soiling, urine dribbling; sometimes facial nerve deficits.

What to do now: protect skin from scald, ensure hydration, call your vet.

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): clinical pattern; anti-inflammatories, nursing care.

Prognosis: guarded; relapses possible.

Temporohyoid Osteoarthropathy (THO)

Bony change near the ear joint stresses cranial nerves (VII, VIII).

What you’ll see: facial paralysis, inability to blink, head tilt, ear pain; risk of corneal ulcers.

What to do now: protect the eye (keep it lubricated if you’ve been trained), minimize halter pressure behind ears, urgent vet call.

Diagnosis & care (vet-led): imaging; anti-inflammatories/antimicrobials; surgical options; intensive eye care.

Prognosis: variable; eye protection is time-critical.

What to record before your vet arrives

Video: straight line, small circles both ways, backing, and a short hill if safe.

Timeline: first day you noticed signs; any fever, new horses, travel, diet changes.

Vitals: temperature, heart rate, respiration, mucous membranes (compare to your horse’s normal). See: The Horse’s Vital Signs.

Safety: no riding, no sedation without vet direction; protect eyes/skin if blinking or tail tone is poor.

Keep learning: The Equine Nervous System: Part 2 — Diving Deeper (reflex grading, assessment flow).

The Nervous System and Training

Training “works” because you’re shaping how the horse’s nervous system senses, processes, and responds to the world. The same circuits that drive flight, balance, and habit formation determine whether a cue is crisp or confusing. Use the principles below to make learning faster, calmer, and safer.

1) Startle → Settle: managing the flight system

Horses are prey animals; the sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) branch fires first. Productive training keeps arousal below the threshold where thinking shuts off.

Use approach–retreat and graded exposure: show the stimulus small → retreat → repeat slightly bigger.

Reward the moment of down-shift (breath out, head lowers, ear softens). That’s the parasympathetic system coming online—learning happens here.

If startle escalates, reset the context (distance, intensity, duration), then try again.

Cross-check recovery with baselines: The Horse’s Vital Signs and Average Heart Rate.

2) Learning & memory: how cues “stick”

The cerebrum builds associations; the cerebellum polishes timing and smoothness.

One cue → one meaning. Stack aids in a consistent order; remove extras as soon as the horse offers the try.

Short, frequent reps beat long marathons (fatigue raises error rates and stress chemistry).

Mark the exact behavior (a calm “good” or click), then follow with a reward the horse values (release, rest, scratch, or food if appropriate).

3) Sensory processing: make pressure readable

The nervous system learns by contrast. If your signal is noisy or always “on,” the horse can’t find the right answer.

Start with the lightest aid; escalate smoothly; the release teaches.

Change one variable at a time (location, speed, surface, company) so the brain can generalize the cue without confusion.

4) Coordination & balance: build the wiring you want

Smooth gait transitions, straightness, and rhythm are cerebellar wins.

Use slow practice to build fast control: deliberate walk work, poles, and large circles before adding speed or collection.

Film short sets; look for toe drag, hind-end swing, or inconsistent placing. If these persist at easy effort, investigate—see Part 2 for assessment flow.→ Keep learning: Equine Nervous System: Part 2 — Diving Deeper.

5) Stress chemistry: train the state you want to ride

Chronic sympathetic dominance blunts learning and immunity.

Build predictable session structure: warm-up → skill blocks (3–5 min) → decompression.

End on a truthful win (a small, clean rep) to anchor memory in a calm state.

6) Troubleshooting map

Over-reactive or “spooky” today? Shrink the task; chase the down-shift first. Reward relaxation before retrying the skill.

Dull to the leg/hand? Check clarity and timing of release; re-install light cue on the ground, then saddle.

Sudden tripping, head tilt, uneven blink, trouble swallowing, or asymmetrical weakness? These are neurological red flags—stop and call your vet. Use your vital signs to judge urgency.

7) Simple barn drills to hard-wire calm responses

Breathe-to-release pairing: Exhale → soften reins/leg → horse steps down a gear. Name it (“easy”).

Targeting/parking: Teach stand-still with a nose target or ground spot; build duration in seconds, not minutes.

Patterning for confidence: Repeat an easy line (e.g., centerline → big circle) until rhythm is automatic, then add one small change.

Bottom line: Good training is nervous-system training. Keep cues clear, reps short, arousal controlled, and releases honest—and use objective baselines (vital signs, heart rate) to separate “training problem” from “potential neuro issue.”

Summary table

Component / Concept | What it Does | Signs It’s Off | Training Application | Action Cue |

Cerebrum | Perception, decisions, learned responses | Behavior shifts, misreading cues, abnormal reactions | Keep one cue → one meaning; short frequent reps; mark & release precisely | If behavior changes + dull/odd mentation, note vital signs and call vet |

Cerebellum | Balance, timing, fine motor control | Exaggerated steps, overshooting, pole knock-downs | Slow practice → fast control; large circles, poles, rhythm focus | Persistent incoordination at easy effort → vet; see Part 2 |

Brainstem | Autonomic control (breathing, swallowing, HR) | Dysphagia, abnormal breathing, profound lethargy | Keep arousal low; stop work if swallow/breathing off | Urgent: swallowing or breathing problems → vet now; check HR |

Cervical Spinal Cord | Neck & forelimb pathways | Toe-drag/stumble in front; worse on small circles | Address footing and clarity; video straight vs circle | Neuro-style tripping persists → vet assessment |

Thoracic/Lumbar SC | Trunk stability & hindlimb coordination | Hind swings wide, trouble backing straight | Straightness drills; poles; core-stability patterns | If inconsistent placing remains at walk/trot → vet |

Sacral SC | Tail tone, pelvic/perineal function | Flaccid tail, incontinence, breeding issues | N/A – medical domain | Medical/urgent depending on severity → vet |

Cranial Nerves (I–XII) | Vision, balance, swallow, facial movement | Head tilt, uneven blink, dropped feed | Simple barn checks: menace, palpebral, tongue tone | Any deficit → document + vet; see Part 2 flow |

Sensory (Afferent) | Brings info in (touch, pain, position) | Over/under-reacts to stimuli; inconsistent placing | Start with lightest aid; change one variable at a time | If sudden sensory change (e.g., vision/balance) → vet |

Motor (Efferent) | Sends commands to muscles | Weakness, delayed response, dragging | Reward the release; install light response on ground first | New weakness/asymmetry → vet |

ANS – Sympathetic | “Fight-or-flight,” arousal | Spookiness, tension, sweaty with light work | Approach–retreat, reward down-shift moments | If cannot down-shift at rest → stop, reassess health |

ANS – Parasympathetic | “Rest-and-digest,” recovery | Dullness, poor gut sounds, low engagement | Build predictable sessions; end on a calm win | Pair observations with vitals; call vet if abnormal |

Self Assessment Quiz

Multiple Choice Questions

What are the two main divisions of the equine nervous system?

a) Brain and spinal cord

b) Central Nervous System and Peripheral Nervous System

c) Sensory and motor nerves

d) Autonomic and somatic systems

Which part of the brain is responsible for coordination and balance?

a) Cerebrum

b) Cerebellum

c) Brainstem

d) Medulla Oblongata

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) controls:

a) Voluntary muscle movement

b) Reflexes only

c) Involuntary functions like heart rate and digestion

d) Conscious thought and decision-making

Which of the following diseases affects the equine nervous system?

a) Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis (EPM)

b) Laminitis

c) Colic

d) Cushing’s Disease

A horse’s fight-or-flight response is primarily controlled by which part of the nervous system?a) Parasympathetic Nervous System

b) Sympathetic Nervous System

c) Somatic Nervous System

d) Reflex Arc

True/False

___ The cerebrum is the largest part of the horse’s brain and is responsible for conscious thought and decision-making.

___ The spinal cord controls reflex actions without involving the brain.

___ Horses have 24 pairs of cranial nerves.

___ Damage to the cranial nerves can result in loss of coordination or difficulty swallowing.

___ The equine nervous system plays no role in training or behavior.

___ Chronic stress can negatively impact the horse’s nervous system and overall health.

Short Answer

Name two key reflexes in horses and their function.

What is the difference between the Central Nervous System (CNS) and the Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)?

How does the nervous system influence horse training and behavior?

List one neurological disorder in horses and describe its symptoms.

How does the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) help maintain a horse’s internal balance?

FAQ: Understanding the Equine Nervous System

What are the main components of the equine nervous system?

The equine nervous system comprises two primary divisions:

Central Nervous System (CNS): Consists of the brain and spinal cord. The brain processes information and coordinates responses, while the spinal cord transmits signals between the brain and the rest of the body.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS): Includes all nerves outside the CNS. It connects the CNS to limbs and organs, facilitating communication throughout the body. The PNS is further divided into the somatic nervous system, controlling voluntary movements, and the autonomic nervous system, regulating involuntary functions like heart rate and digestion.

How does the autonomic nervous system affect a horse's behavior?

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) operates subconsciously, managing vital functions such as heart rate, respiratory rate, and digestion. It has two branches:

Sympathetic Nervous System: Activates the "fight or flight" response during stressful situations, increasing heart rate and redirecting blood flow to essential muscles.

Parasympathetic Nervous System: Promotes "rest and digest" activities, conserving energy and facilitating routine bodily functions.

An imbalance in the ANS can lead to behavioral issues, such as heightened anxiety or lethargy, affecting a horse's performance and well-being.

What role do cranial nerves play in a horse's daily functions?

Horses possess 12 pairs of cranial nerves that emerge directly from the brain, each serving specific functions:

Olfactory Nerve (I): Sense of smell.

Optic Nerve (II): Vision.

Facial Nerve (VII): Facial expressions and taste sensations.

Vagus Nerve (X): Controls heart rate, digestion, and respiratory rate.

These nerves are crucial for sensory perception and motor control, impacting behaviors like eating, vocalizing, and responding to environmental stimuli.

How do sensory and motor nerves function in horses?

Sensory (Afferent) Nerves: Transmit information from sensory receptors to the CNS, allowing horses to perceive touch, temperature, pain, and body position.

Motor (Efferent) Nerves: Convey commands from the CNS to muscles, facilitating movement and coordination.

This bidirectional communication enables horses to interact effectively with their environment, maintaining balance and executing complex movements.

What are common signs of neurological disorders in horses?

Neurological issues in horses can manifest through various symptoms, including:

Ataxia: Uncoordinated movements or stumbling.

Muscle Weakness: Difficulty in standing or moving.

Behavioral Changes: Unusual aggression or depression.

Cranial Nerve Deficits: Drooping facial features or difficulty swallowing.

Prompt veterinary assessment is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment of neurological conditions.

How does the nervous system influence a horse's training and performance?

The nervous system governs a horse's ability to learn, respond to cues, and perform tasks. A well-functioning nervous system ensures:

Efficient Signal Transmission: Quick responses to rider commands.

Muscle Coordination: Smooth and precise movements.

Stress Management: Appropriate reactions to environmental changes.

Understanding the nervous system's role can help trainers develop effective training programs that enhance performance while ensuring the horse's comfort and safety.

Comments