Splint Bone Injuries, an Advanced Overview

- Horse Education Online

- Jan 22

- 6 min read

Anatomical Overview

The splint bones are located on the palmar aspect of the cannon bone (metacarpus) in the fore limbs, and the plantar aspect of the cannon bone (metatarsus) in the hind limbs. The cannon bone, or third metacarpal bone, is the primary weight-bearing structure of the distal limb of the horse. Splint bones are considered vestigial, meaning they are underdeveloped remnants of what were once fully weight-bearing digits in the horse’s evolutionary ancestors. Anatomically, they are identified as the second and fourth metacarpal or metatarsal bones, which flank the centrally positioned cannon bone.

Forelimb Anatomy

The medial splint bone is also called the second metacarpal bone. It lies on the inside of the limb and is clinically the most commonly affected splint bone due to biomechanical loading and interference.

Medial splint bones are under greater biomechanical stress as they lie closer to the centerline of the body, and therefore bear greater weight. For this reason, the head of the medial splint bones has two facets to better support the carpal bones.

Medial splint bones are additionally at greater risk of traumatic injury from the horse striking itself with the opposing limb or hoof. Learn more about interfering, the gait fault that most commonly leads to splints, here.

The lateral splint bone is the fourth metacarpal bone and lies on the outside of the limb, where it is more susceptible to external trauma. Its head is one-faceted.

Hindlimb Anatomy

The medial splint bone in the hind limb is the second metatarsal bone, positioned on the inside of the hind limb. Just like in the forelimb, the medial splint bone is under greater biomechanical stress, and therefore has a two-faceted head to support the tarsal bones.

The lateral splint bone is the fourth metatarsal bone, located on the outside of the limb. It's head is one-faceted.

The splint bones taper progressively as they extend distally from the carpal or tarsal joint. Near their distal ends, they form a palpable bony enlargement, commonly referred to as a “button” or nodule, located several centimeters proximal to the fetlock joint. Throughout their length, the splint bones run parallel to the cannon bone, contributing to the longitudinal stability of the limb.

Ligamentous and Fascial Attachments

Splint bones are attached to the cannon bone via the interosseous ligament, a fibrous structure that provides both support and limited mobility. In young horses, this ligament allows a small degree of motion between the splint and cannon bones, which is thought to help dissipate concussive forces during locomotion.

The interosseous ligament varies considerably between individual horses in terms of thickness and elasticity. With age and continued mechanical stress, this ligament typically undergoes progressive ossification, reducing mobility between the bones.

In some older horses, partial or complete fusion of the splint bone to the cannon bone may occur. While often clinically insignificant, this fusion reflects long-term adaptation to repetitive stress.

A dense layer of fascia overlies the tendons in the proximal metacarpal and metatarsal regions and attaches directly to the splint bones. Fascia is a critical connective tissue system that wraps, supports, and separates muscles, bones, and organs, while also contributing to force transmission, coordinated movement, and sensory feedback.

A band-like structure extends distally from the end of each splint bone toward the proximal sesamoid bones, further integrating the splint bones into the suspensory apparatus of the distal limb.

Articulations

The heads of the splint bones serve as a structural platform for the lower row of carpal or tarsal bones, contributing to joint stability. As previously discussed, medial splint bones have a two-faceted head, while lateral splint bones have a one-faceted head. This is to account for the additional stress placed on the medial splint bone as it lies closer to the centerline of the body.

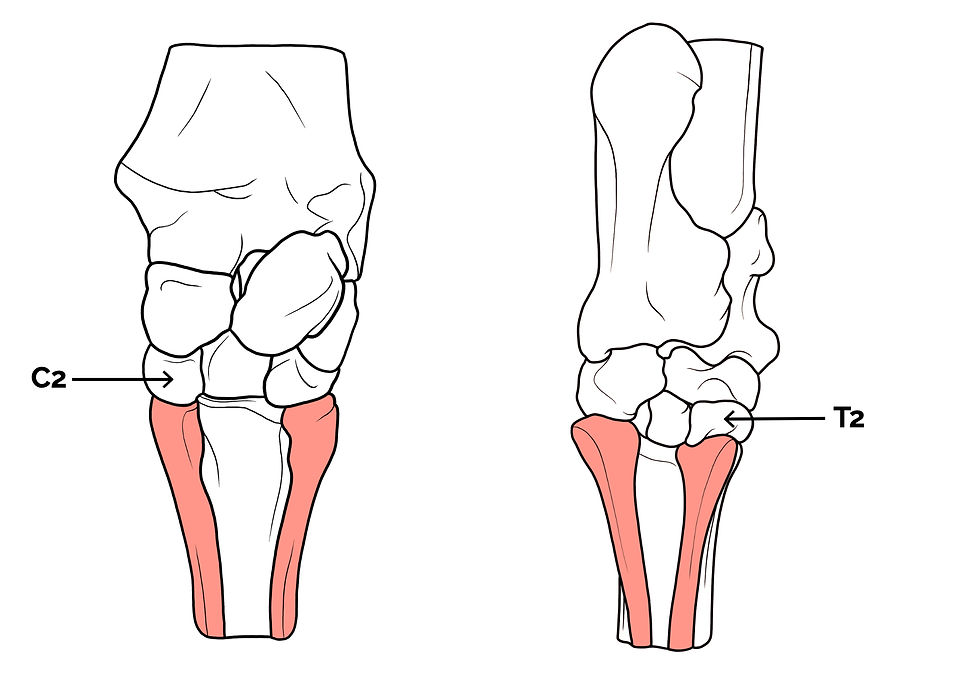

The medial splint bone forms a full articulation with the second carpal bone (C2) in the forelimb and the second tarsal bone (T2) in the hindlimb. This complete articulation explains why pathology of the medial splint bone may be associated with adjacent joint discomfort. Download our Tarsus and Carpus flashcards to study tarsal and carpal anatomy in depth.

The splint bones in relation to the carpal and tarsal bones (palmar/plantar view) The lateral splint bone supports only half of the fourth carpal bone, making it less involved in weight-bearing but more vulnerable to trauma.

Classification of "Splints"

A splint is defined as a bony enlargement (exostosis) involving the second or fourth metacarpal or metatarsal bones. An exostosis is a benign proliferation of bone that develops in response to stress, inflammation, or trauma.

Three primary types of splints are recognized:

Intermetacarpal / Intermetatarsal Splint

This form involves an exostosis developing between the cannon bone and a splint bone. It is commonly associated with injury or inflammation of the interosseous ligament and represents the most frequently encountered splint type in clinical practice.

Intermetacarpal / Intermetatarsal splint Postmetacarpal / Postmetatarsal Splint

This splint occurs on the palmar or plantar (axial) surface of a splint bone. Its location may place it closer to important soft tissue structures, increasing the potential for clinical significance.

Postmetacarpal / Postmetatarsal splint Blind Splint

A blind splint is an exostosis on the axial (central) surface of a splint bone that cannot be detected by palpation and is not visible on standard radiographs. These splints may still cause lameness, particularly if they impinge on the suspensory ligament.

Blind Splint

Green Splints

The term “green splint” refers to an actively forming splint characterized by heat, swelling, and pain on palpation.

At this stage, inflammation is still present, and bone remodeling is ongoing.

Most green splints produce a mild Grade 3 lameness when the horse is trotted on a firm surface in a small circle.

Once inflammation resolves and pain is no longer present, the splint is considered “set” and is no longer classified as a green splint.

Radiographic examination is essential to:

Determine the size and exact location of the splint

Identify any associated fractures of the splint bone

Etiology

Interosseous Ligament Injury

Tearing or inflammation of the medial interosseous ligament commonly occurs when horses are first placed into structured work.

The ligament is not yet conditioned to repetitive loading, making it particularly vulnerable during early training.

Physical Trauma

Young horses frequently strike the medial splint bone with the opposing limb while playing, leading to localized inflammation or tearing.

Lateral splint bones are more susceptible to trauma from external sources such as other horses or solid objects.

Medial splint bones are most often injured by interference from the contralateral limb.

Conformation-Related Stress

Conformational abnormalities such as base-narrow stance, toed-out feet, angular limb deformities, and offset knees increase mechanical strain on the medial splint bone.

These conformations promote inward limb motion and increase stress on the medial interosseous ligament.

Training Factors

Excessive work in tight circles, particularly in young horses, concentrates force on the medial splint bone.

Repetitive strain can lead to ligament tearing followed by reactive bone formation as part of the healing process.

Diagnosis

Splints are diagnosed through a combination of clinical examination, lameness evaluation, and diagnostic imaging, with the goal of confirming the presence of a splint, determining its stage of development, and identifying any associated complications.

Diagnosis begins with a thorough physical examination of the limb. Palpation of the splint bones may reveal localized heat, swelling, or pain, particularly in cases of green splints. Firm, non-painful bony enlargements suggest a set splint. Careful comparison with the contralateral limb is essential, as mild splints may be subtle.

Diagnostic imaging, particularly radiography, is central to definitive diagnosis. Radiographs allow visualization of bony proliferation, assessment of the splint’s size and location, and identification of splint bone fractures. Imaging is especially important when lameness is disproportionate to palpable findings or when a blind splint is suspected.

Treatment

Conservative Management

Rest for several weeks is the most effective treatment and allows inflammation to resolve and bone remodeling to stabilize.

After the acute phase, light exercise on soft footing may promote controlled healing.

Counter-irritants are not recommended, as they increase inflammation, disrupt orderly bone formation, and may prolong recovery time.

Surgical Intervention

Splint bone fractures, particularly those involving the distal one-third, are most appropriately treated surgically.

Surgical removal of splint bone enlargements in show horses often yields poor outcomes, as surgery may stimulate additional bone formation.

Approximately 50% of these procedures are considered successful.

Prognosis

In cases that do not involve blind splints impinging on the suspensory ligament or high splint bone fractures, the prognosis is excellent.

Pain typically resolves rapidly, although the bony enlargement may persist as a cosmetic blemish.

Over time, gradual bone remodeling may occur, and the splint may become minimally noticeable or clinically insignificant.

Comments